Ecce Homo is book #223 from The Literary Project.

Ecce Homo is technically considered an autobiography, although it must be pointed out that there is much to be desired in terms of what one usually expects from a biographical account. Life events and facts within the text can be counted on one hand. Instead, it is a curriculum vitae of his philosophical works, mired in hubris with such chapter titles as “Why I Am So Clever” and “Why I Write Such Good Books.” Ultimately, it serves an educative function: to put himself forth as a role model for self-becoming; a living blueprint of his philosophy.

Rewriting the Past: Amor Fati

“Amor Fati” is a “love of fate,” a retrospective reflection on one’s life experiences to actively overcome the parts that are no longer of yourself–to deem events that were inauthentic to the self as necessary stages in one’s life trajectory; to love them because they are leading you to your fate, to your becoming what Nietzsche coined as an “overman”.

“My formula for human greatness is amor fati: not wanting anything to be different, not forwards, not backwards, not for all eternity. Not just enduring what is necessary, still less concealing it–all idealism is hypocrisy in the face of what is necessary–but loving it…”

(section 10 in “Why I Am So Clever”)

Nietzsche’s concept of Amor Fati differs from the Stoics’ in that the Stoics used Amor Fati to look at and accept the world as it arrived, in the present moment within their present life conditions; whereas Nietzsche used Amor Fati as a way to re-write his past in a very post-modern sense of the word: experiential rather than factual. He claims “not wanting anything to be different,” except that he regularly looked back on his life and re-created “all ‘It was’ into a ‘thus I willed it!'”

In this way, Nietzsche became the unreliable narrator of his own life. One can ask of all biographical accounts: how accurate are memories anyway? The flawed nature of human memory means that we must take all biographies with a grain of salt but, considering Nietzsche’s Amor Fati worldview, this is especially the case for Ecce Homo.

Seeking Truth: “I Am Dynamite”

In the Forward, Nietzsche makes a bid to the reader to walk towards knowledge with courage and away from the cowardice of blindly following a societal ideal.

“The lie of the ideal has till now been the curse on reality; on its account humanity itself has become fake and false right down to its deepest instincts.”

(section 2 of the Forward)

As one continues to read on, it becomes clear that what he means by this dark “ideal” is, in fact, Christian morals:

“Christian morality–the most malignant form of the will to falsehood, the true Circe of humanity: the thing that ruined it.’

(section 7 in “Why I Am Destiny”.)

To Nietzsche, religion is anti-thought:

“I am too curious, too dubious, too high-spirited to content myself with a rough-and-ready answer. God is a rough-and-ready answer, an indelicacy against us thinkers–basically even just a rough-and-ready prohibition on us: you shall not think!”

(section 1 in “Why I Am So Clever”)

Religion stands in direct opposition to his urging for one to constantly test and reexamine common conceptions in the world: the “self-overcoming of [Christian] morality out of truthfulness.” One should question in order to discover truthfulness for oneself, to “self-overcome”, rather than to be told what it is.

Because he considers himself to be “the first to discover the truth, by being the first to sense–smell–the lie as a lie…” (section 1 in “Why I Am Destiny”), he calls himself the Antichrist and refers to himself thus:

“I am the first immoralist: hence I am the destroyer par excellence.”

(section 2 in “Why I Am Destiny”)

And, thus, he uttered his famous words:

“I am not a man, I am dynamite.”

(section 1 in “Why I Am Destiny”)

Growth: Self-Becoming Into An Overman

Finally, in addition to practicing Amor Fati and seeking truth beyond religious falsehoods, self-becoming entails allowing a “higher concern” to germinate and grow toward the formation of an overarching life purpose. In other words, self-becoming can be thought of as self-actualization. It is more than simply being yourself; it is a striving development on the road to becoming an impeccable human being, an “overman.”

“Meanwhile, in the depths, the organizing ‘idea’ with a calling to be master grows and grows–it begins to command, it slowly leads you back out of byways and detours, it prepares individual qualities and skills which will one day prove indispensable as means to the whole–it trains one by one all the ancillary capacities before it breathes a word about the dominant task, about ‘goal’, ‘purpose’, ‘sense’.”

(section 9 in “Why I Am So Clever”)

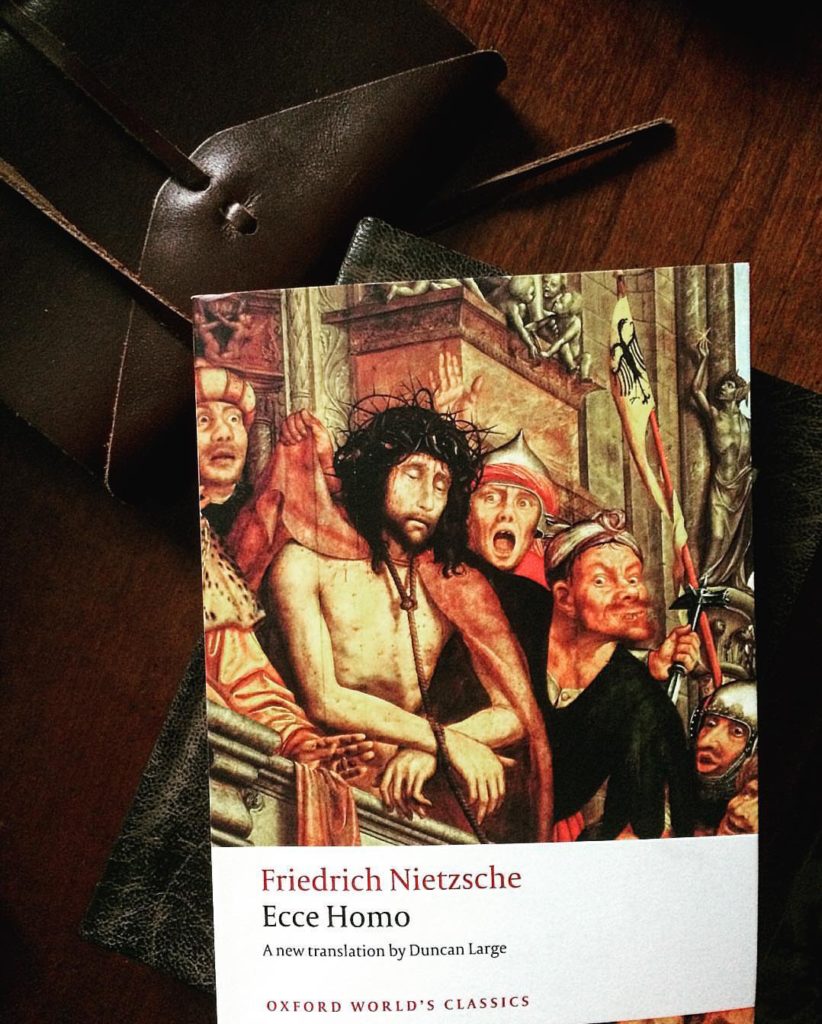

“Ecce Homo” is Latin for “Behold the Man!” They were the words spoken by Pontius Pilate when he presented Christ before his accusers, before the Crucifixion. Pilate says the words mockingly, but Nietzsche–the self-proclaimed Antichrist–claims the phrase for himself in both a show of irony and in a declaration of his status as the ultimate Overman.