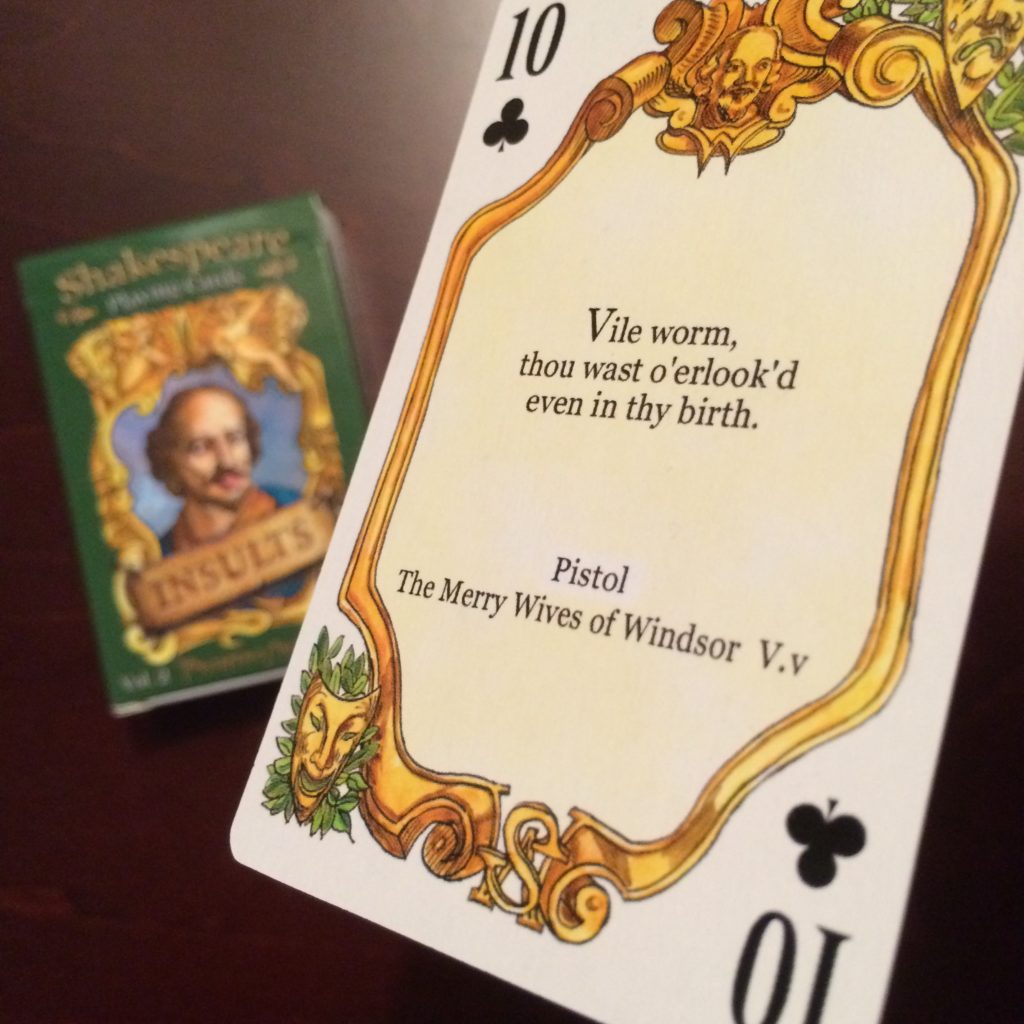

This essay was part of the 2016 Deal Me In Reading Challenge, where I read a short story, essay, or poem every single week. Each item on my reading list was assigned to a playing card, and every Friday I picked a card at random to choose my weekly read.

The Erasure of Black Women is a look at the intersection of race and gender, and the resulting exclusion of black women in such cultural discussions; not just by those entrenched in the patriarchal psyche that is so prevalent in our culture, but even by the feminists who habitually step outside of that thought paradigm.

The Additive Analysis Fallacy

One of the concepts that Spelman explores in this essay is the erroneous idea where race and gender are two separate things that add on linearly to make up the experience of black women in our society.

“Reflection on the experience of black women also shows that it is not as if one form of oppression is merely piled upon another. As Barbara Smith has remarked, the effect of multiple oppression ‘is not merely arithmatic,’…”

There is the black man’s experience and there is the white woman’s experience, and rather than the black woman’s experience being a third equally valid option, many intellectuals in the feminist thought sphere treat the black woman’s experience as the equivalent of the former two added together–treating it as though it does not stand on its own as a separate and unique experiential entity.

“An additive analysis treats the oppression of a black women in a sexist and racist society as if it were a further burden than her oppression in a sexist but non-racist society, when, in fact, it is a different burden…to ignore the difference is to deny or obscure the particular reality of the black woman’s experience.”

She disputes the claim by many intellectuals who have claimed that sexism is a more fundamental issue than racism. She paraphrases this idea thus:

“What is really crucial about us is our sex; racial distinctions are one of the many products of sexism, of patriarchy’s attempt to keep women from uniting. It is through our shared sexual identity that we are oppressed together it is through our shares sexual identity that we shall be liberated together.”

But once again, black women are not oppressed the same way as white women. To say that they are both oppressed only as women, is a fallacious claim:

“A serious problem in thinking…this way, however, is that is seems to deny or ignore the positive aspects of ‘racial’ identities. It ignores the fact that being black is a source of pride, as well as an occasion for being oppressed. It suggests that once racism is eliminated, black women no longer need be concerned about or interested in their blackness–as if the only reason for paying attention to one’s blackness is that it is the source of pain and sorrow and agony. But that is racism pure and simple, if it assumes that there is nothing positive about having a black history and identity…”

Somatophobia

Spelman goes on to discuss somatophobia–fear & devaluation of the body. Ever since cultured humans evolved from our brutish cavemen ancestors, mankind has devalued the body and glorified the mind. White men distanced themselves as much as possible from the hassles of bodily realities while only choosing to engage in its pleasures. But so long as we are human, bodily maintenance must be attended to. And so if white men are not attending to it, then that means the responsibility gets forced on to those who are not upper class white men:

“…the idea that the work of the body and for the body has no part in real human dignity has been part of racist as well as sexist ideology. That is, oppressive stereotypes of ‘inferior races’ and of women have typically involved images of their lives as determined by basic bodily functions (sex, reproduction, appetite, secretions and excretions) and as given over to attending to the bodily functions of others (feeding, washing, cleaning, doing the ‘dirty work’). Superior groups, we have been told from Plato on down, have better things to do with their lives.”

Sexist and racist belief in an inferiority of the minds of women and people of color is the reason why those groups have been chosen to do the “dirty work”:

“Neither in women nor in slaves does the rational element work the way it ought to. Hence women and slaves are, though in different ways, to attend to the physical needs of the men/masters/intellectuals…”

At this point, I could not help but think of the women of Jane Austen’s novels, and how they were esteemed for their intellectual accomplishments. But then again, they are of the upper leisure class, which means that, at some point, somatophobia became not only about race and gender, but of class as well:

“…somatophobia historically has been symptomatic of sexist and racist (as well as classist) attitudes.”

But the solution is not for women to liberate themselves by divorcing their associations with bodily work:

“…when a group views it liberation in terms of being free of association with, or responsibility for, bodily tasks…its own liberation may be predicated on the oppression of other groups–those assigned to do the body work. For example, if feminists decide that women are not going to be relegated to doing such work, who do we think is going to do it?”

Such work must be done, and so modern-day feminist thought is beginning to realize that it is not enough for women to go out into the intellectual world; men must also step up responsibility within the bodily household and child care duties. Movement, in other words, must go both ways–body work and mind work must be shared across all groups. So long as any group continues to feel that body work–“women’s” work!–is beneath them, they actively engage in holding themselves superior.

In terms of race, we’ve seen the rise of the Latino manual laborer and Latina house maid. They are the group who has begun to take over bodily tasks. Sure it is paid labor, but it is low in pay–and that is, once again, due to the devaluing of bodily work. The work of the mind is considered more valuable; the work of the body is not considered “skilled.” But is “skill” truly the only thing to be valued? Is bringing life-giving food to the table truly less “valuable”? Is cleaning our home so that we ourselves have more time to spend with our loved ones truly less “valuable”? What, specifically, makes work “valuable”? Is such value inherent, or is it determined by externally applied social conditioning?

Spelman’s essay is truly thought-provoking. And she–wisely–does not claim to know all the answers. She does, however, point out what the solution is not:

“…the solution may seem to be: keep the person and leave the occasion for oppression behind. Keep the woman, somehow, but leave behind her women’s body; keep the black person but leave the blackness behind…”

But…

“Without bodies we could not have personal histories…without them we could not be identified as woman or man, black or white.”

And aren’t those all things that make us beautiful?

Elizabeth V. Spelman

Spelman is a Philosophy professor at Smith College. She has authored 3 books, and has another forthcoming this spring.